Gov. Sam Brownback’s supply-side economics experiment in Kansas is over.

Last week, the Republican-controlled Kansas legislature took the remarkable step of overriding the governor’s veto, finally repealing his signature tax cuts. Those tax cuts, which reduced personal income tax rates and imposed no tax at all on many kinds of business income, went into effect in 2013, and were touted by Brownback and other leading supply-side figures as the best way to boost growth, bring back jobs, and make Kansas richer.

But now, almost five years into Brownback’s “real live experiment” in trickle-down economics, the evidence from the experiment is in. Brownback’s hypothesis about taxes and growth was decidedly not proved. And even Kansas Republicans have had enough.

On the day that the tax cuts were enacted, the Kansas City Star ran a story in which the governor’s revenue secretary, Nick Jordan, promised that the tax cuts would yield big benefits for Kansas. It’s worthquoting a paragraph from that report in full,sinceitsetsoutBrownback’sowntermsforhistax”experiment”:

“Nick Jordan, the state’s revenue secretary, said the administration ultimately imagines the creation of 22,000 more jobs over ‘normal growth’ and 35,000 more people moving into the state over the next five years. And he expects the tax changes to expand disposable income by $2 billion over the same period.”

There are three specific claims in there: one about jobs, one about population, and one about disposable income. Let’s take them one at a time and see how they panned out.

Job growth lagged in Kansas

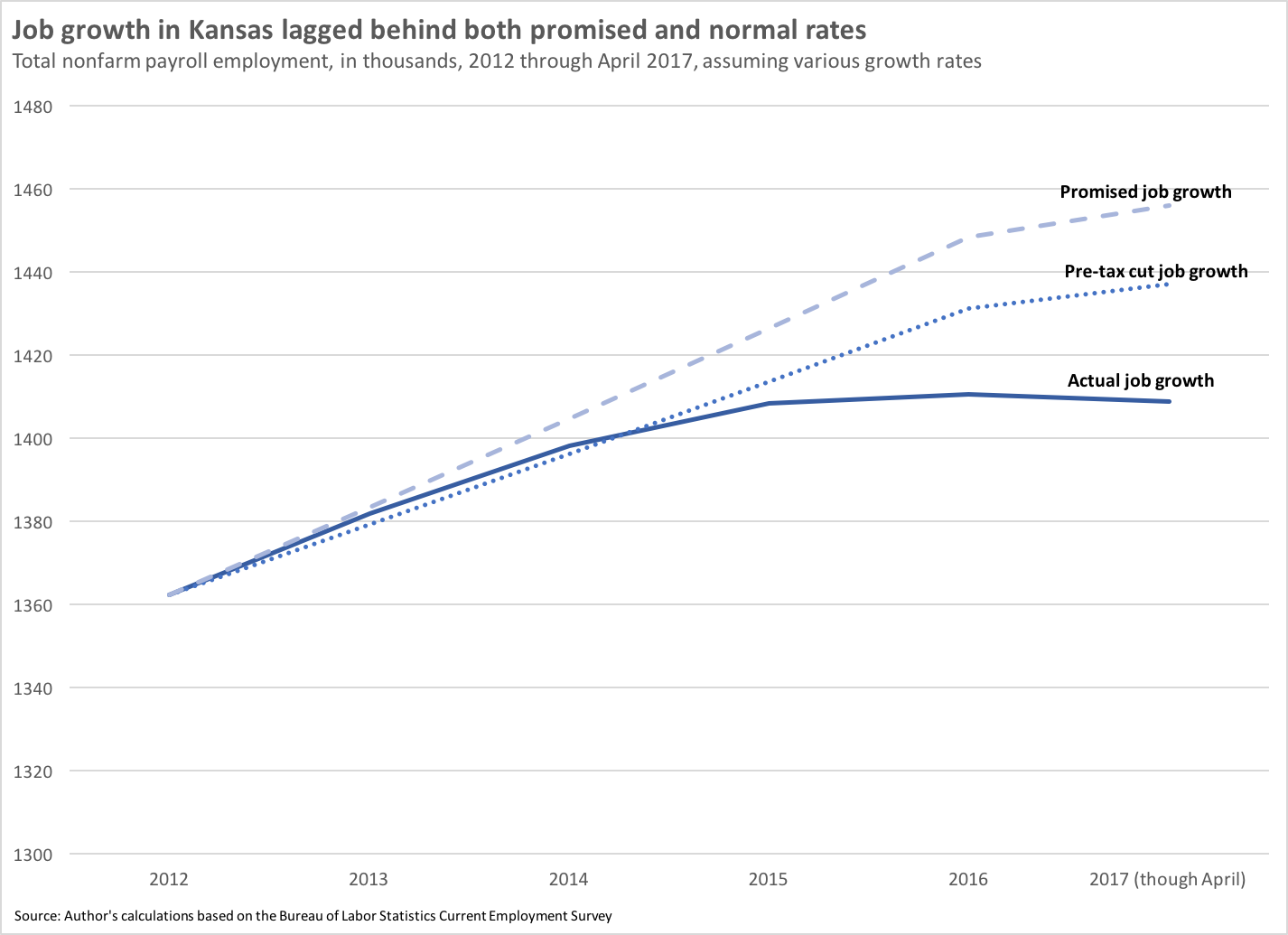

Jordan promised that the tax cuts would yield, "22,000 more jobs over 'normal growth'," within five years. To evaluate how the tax cuts did, we first need to figure out what "normal growth" looks like.

In the five non-recession years prior to the tax cuts, job growth in Kansas averaged about 1.2% annually. If we take that as the normal growth rate, and it had kept up from 2013 through today, we would expect there to be about 1,437,000 jobs in Kansas by April 2017. Recall that Jordan was promising that the tax cuts would add an additional 19,000 jobs on top of that (not the full 22,000, because we're not quite at the end of the five-year period yet) bringing the total up to 1,456,000. That's the benchmark for jobs.

In reality, as of April, Kansas had just 1,409,000 jobs, so not only did the tax cuts fail to add 22,000 extra jobs, job growth actuallydeclinedafter the tax cuts went into effect. As of April, Kansas was 47,000 jobs short of delivering on Secretary Jordan's promise.

It's also important to note that the decline in job growth was unique to Kansas, and not a general trend affecting other nearby states. Kansas's four neighboring states, Colorado, Nebraska, Missouri, and Oklahoma, saw their job growth rate actually increase slightly in the 2013-2017 period compared to the five non-recession years prior to 2013.

Therefore, it's fair to say that on the first metric, "22,000 new jobs," the tax cuts can be considered a dismal failure.

Population growth lagged in Kansas

Jordan also promised that the tax cuts would draw more people to move to Kansas, adding an additional 35,000 people over how many would be expected without the tax cuts.

As with the job growth claim, to evaluate the efficacy of the tax cuts, we first have to start with an estimate of "normal" population growth. From 2008 through 2012, the total population in Kansas grew by an average of about 0.8% each year. If that "normal" growth rate had continued in the four years after the tax cuts, we would expect there to be 2,909,000 people in Kansas by 2016.

Adding in the promised additional population (28,000 instead of 35,000 since 2016 is only four years after the tax cuts, not five) yields a target population of 2,937,000. That's the benchmark for population.

Just as with job creation, the tax cuts utterly failed to produce anything remotely close to that population growth.

In 2016, the population in Kansas totaled 2,852,000. That's 85,000 fewer than Jordan had promised.

And again, that can't be blamed on a general trend of slower population growth in the region. Kansas's four neighboring states also experienced annual average population growth of 0.8% from 2008 to 2012, nearly identical to the growth rate in Kansas, but their growth rate increased slightly in the following four years to 0.9%, compared to Kansas's which dropped substantially.

So far, Secretary Jordan has gone zero for two.

Disposable income growth also lagged in Kansas

The final of the three claims that Jordan made when the tax cuts were enacted was that disposable income would increase by $2 billion relative to a future without the tax cuts.

Given the clear failure of the tax cuts to produce more jobs or faster population growth, you can probably guess how successful the tax cuts were in generating more disposable income for Kansans.

In the four non-recession years prior to 2013, disposable income in Kansas grew by an average of about 5.5% each year. If that growth rate had continued in the four post-tax cut years, then we would have expected disposable income in Kansas to exceed $144 billion in 2016.

Add in the promised $1.6 billion in additional income resulting from the tax cuts and the target for 2016 should have been about $146 billion. But in fact, disposable income in Kansas in 2016 totaled less than $127 billion, nearly $20 billion short of the goal.

In other words, just like with jobs and population, the rate of growth for disposable income not only failed to rise after the tax cuts were put in place, it actually declined substantially.

In this case neighboring states also experienced a slowdown in the growth of disposable income after 2012, so that could explain at least part of the failure of the Kansas tax cuts to deliver on their promise. But the slowdown in neighboring states was much smaller than it was in Kansas, going from 4.8% average annual growth before 2012 to 3.4% afterwards. In Kansas, by contrast, the average annual growth rate dropped from 5.5% to 2.1%.

All told, not only did the tax cuts fail to deliver faster job growth, faster population growth, or faster disposable income growth, but the growth rates of all three metrics declined noticeably after the tax cuts went into effect. Furthermore, the surrounding states, which did not impose massive tax cuts aimed at the rich, outpaced Kansas on all three measures over the same time period.

An experiment that has failed

Five years ago, Governor Brownback and his allies promised that enacting large tax cuts that were skewed toward the wealthy would have enormous benefits for Kansas. He and his allies promised more jobs, a faster growth rate, more income.

They promised a"shot of adrenaline into the heart of the Kansas economy."

The simple fact is that they utterly failed to produce any of those things.

Job creation actually slowed down, as did population growth and the growth of disposable income. Kansas began to lag behind its neighbors, whereas before the tax cuts, it had matched or even exceeded them.

On these three specific measures that Brownback's administration laid out, his tax cuts failed so spectacularly that it becomes clear how it came to be that 67 Republicans in the Kansas House and Senate rebuked a governor of their own party and rolled back his main legislative accomplishment.

There are lessons here for Trump and national Republicans

The purpose of this analysis is not to humiliate or ridicule those who made or believed Brownback's promises, but rather to hold them accountable.

The idea that cutting taxes especially for the rich will boost growth and make everyone better off remains a central, if misguided, element of many economic proposals. President Trump's tax plan, for instance, includes trillions of dollars in tax cuts that would flow overwhelmingly to millionaires and wealthy corporations.

It even includes a very similar proposal to Brownback's policy of giving a special low tax rate for so-called "pass-through" income.

With the remarkable failure of the Brownback tax cuts in Kansas, we can hope that at least some leaders and economic policymakers will begin to adjust their theories to meet the facts, just as the Republican-controlled Kansas state legislature has done.

Michael Linden is a fellow at the Roosevelt Institute, a liberal think tank, and the Policy and Research Director at The Hub Project. He was formerly a senior policy adviser to Democratic Sen. Patty Murray of Washington.